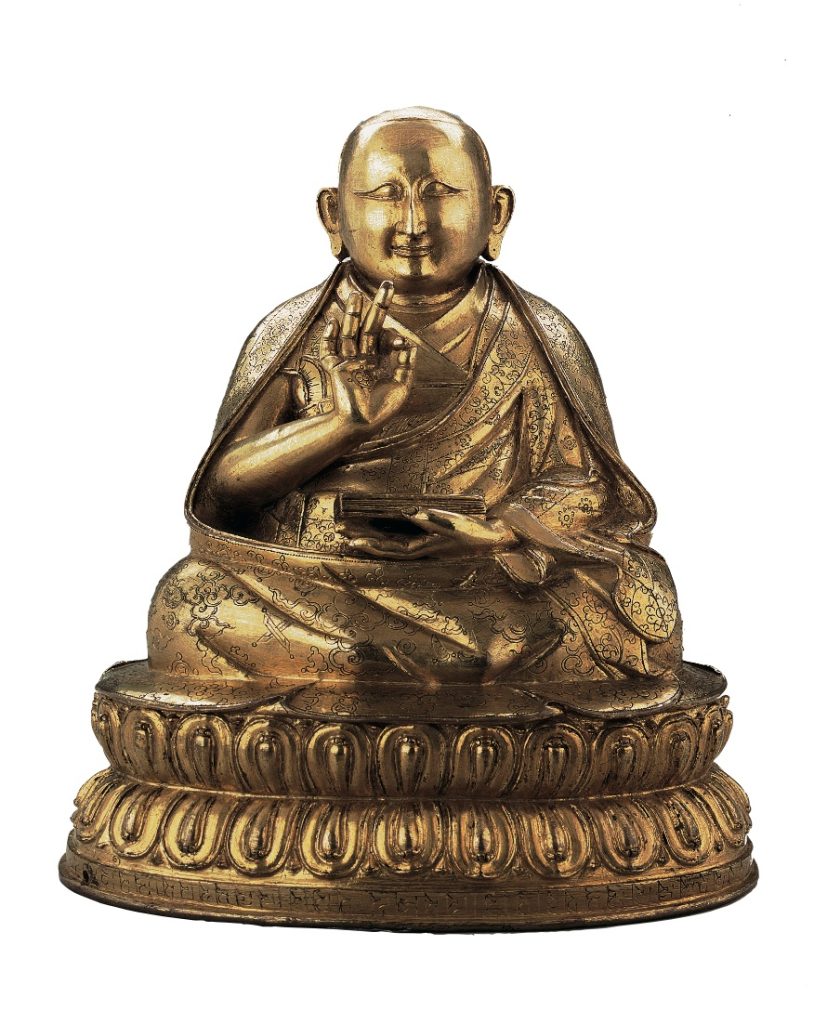

Gilt bronze sculpture of Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Losang Gyatso (1617 – 1682). He was a charismatic figure for both Geluk ad Nyingma orders. He began construction of the Potala Palace on the Red Mountain of Lhasa, the site of the original palace of Songtsen Gambo, the first religious king of Tibet. The Potala stands unsurpassed today as the foremost monument of distinctively Tibetan architecture, a combination of fort, monastery, palace and temple, it has become universally recognized as an emblem of Tibetan Buddhist civilizatiohn. He is seated atop pillows; pillows and robes decorated with incised floral and cloud patterns and geometric symbols. Two crossed dorjes at front of bottom pillow. Almost exactly one thousand years after the time of Emperor Songtsen Gambo, the Fifth Dalai Lama incarnation was found in 1619 in Chongyi, the valley of the ancient Tibetan kings. The exceptional child was born in late 1617, what the Tibetans call the year of the fire snake. Due to the severe military suppression of the Geluk monasteries by the Tsang regent, his presence was kept secret at first. This political tension eased somewhat in 1622, when the old Tsang regent died and the sixteen year old Karma Tenkyong Wangpo took his place. But the new child Dalai Lama was on dangerous ground, as it soon became apparent that the new regent, Tenkyong Wangpo, was planning to totally eradicate the Geluk Order. During the next twelve years, the new ruler made alliances with the Bonpo king of Beri, a country east of Tibet, and a Chogtu Mongol chieftain in order to destroy the Geluk Pa. The advisers of the Fifth Dalai Lama heard of this and approached other Mongol chieftains to protect the order. A special relationship developed between Gushri Khan of the Qoshot Mongols and the young Dalai Lama. When the Chogtu Mongols started the invasion of the central regions of Tibet, they were stopped and defeated by Gushri Khan and his allies. Gushri Khan came to Lhasa in 1638 and publicly proclaimed his support for the Dalai Lama, an act that only intensified the Tsangpa ruler’s plans to eliminate the Geluk Order and its Dalai Lama. Gushri Khan eventually went to Beri and destroyed the king of Beri’s army. The khan then went on the offensive against the Tsangpa ruler in 1641, and conquered him in 1642. In that year, he officially proclaimed the twenty-four-year-old Fifth Dalai Lama the spiritual and temporal ruler of Tibet, from Tachienlu in the east to Ladakh in the west, from Kokonor in the north to the Himalayas in the south.

This story is usually told as just another series of political events. In fact, it has a much deeper significance. In assuming this responsibility, the Fifth Dalai Lama was departing from the Buddha’s original example, set when he abandoned his throne for the monastic life, and from established Tibetan tradition, which would have had him serving as a spiritual hierarch in cooperation with a lay ruler of the secular sphere. Instead, he absorbed the role of Dharma King into his own person as monk-sage and tantric adept rolled into one. Publicly recognized as a reincarnation of Avalokiteshvara, the celestial Bodhisattva of great compassion, he became a union, in one person, of the founders of Tibetan Buddhism, Shantarashitka, Padma Sambhava, and Trisong Detsen: abbot, Great Adept, and king. In 1645 he began to build a new palace on the Red Mountain, mythic site of Avalokiteshvara’s contemplations and historic site of Songtsen Gambo’s palace of one thousand years before. He built the magnificent Potala that we see today, a monument that is at least three buildings rolled into one—monastery, a sacred mandala temple, and fortress seat of government. He set up a unique new form of government, employing monastic and lay officials to work side by side. After the turbulence of centuries of struggle had calmed, he reduced military institutions to the absolute minimum. As the whole land was ritually offered to him as the incarnation of Avalokiteshvara, he was able to create a situation where the Tibetan aristocracy held its privileges not by private military prowess but by service to the government. Each family was required to station its leading members in Lhasa to work for the nation, receiving their ancestral estates as salary for their service of the government. He relied on diplomacy to settle border problems, and he exerted his influence to preserve peace throughout Asia. The Ming dynasty collapsed two years after his enthronement, and the Manchus, a non-Chinese people from the forests north of Korea, conquered China. The Dalai Lama made an alliance based on equality with the Manchu emperor. The Manchus honored the Tibetan ruler greatly, not only because of his religious sanctity but also because they needed his help to keep the Mongols well disposed toward the Manchus.

Intriguingly, it was around the very same century, the 17th, that the seeds of most modern nations around the world were being planted. Louis XIV built Versailles, Peter the Great planned St. Petersburg, the Manchus developed Beijing into a multinational imperial capital, the Tokugawa shogunate was developing Edo, the Mughal and Ottoman empires were at their height, the Spanish and Portuguese were rich with treasure from the New World, and the British were going through revolutionary changes at home, while developing possessions in North America. Newton, Descartes, and Galileo were laying the groundwork for materialistic, mechanistic Western modernity, as Luther and Calvin had prepared the way for Protestant Europe to bring the Industrial Revolution that would conquer the entire planet.

In Europe and Japan, the transformation of the balanced, medieval world into the dynamic, progressive modernity on the march required that the militarily focused secular states swallow all sacred institutions with their monastic focus. The shogunate destroyed Buddhist monasticism in Japan in the late 16th century, and the Protestants destroyed Catholic monasticism in Britain and northern Europe during that same period. According to the well-established analysis of sociologist Max Weber, the disenchantment of the world by the process of secularization was the ideological engine of the utilitarian, capitalistic, engineering rationalism that created the modern world. In fact, this kind of secularized society living in the material world is the only form of modernity we can imagine. All other societies are simply lumped together as pre-modern, or non-Western, not to speak of underdeveloped, backward, and so forth.

But the case of Tibet poses a real challenge to this Eurocentric outlook. At the very same moment that the West was finalising its secular form of rational modernity, the Fifth Dalai Lama was taking steps to transform the inner Asia of Tibet and Mongolia in the precisely opposite direction. There the sacred institutions swallowed the secular state and its military. Tsong Khapa’s followers had developed the enlightenment-oriented, millennial worldview essential to undergird a spiritualistic, organic modernity. The Karmapa Lama and Dalai Lama incarnations of Avalokiteshvara prepared the way for Tibet and Mongolia to complete the monastic revolution and to “industrialize” the Buddhist educational program of self-conquest. Thus the Tibetan worldview dating from this period can be understood as a kind of alternative modernity, a spiritualistic or interior modernity in contrast with the Western materialistic or exterior modernity we are familiar with. It is this different kind of modern quality that makes Tibetan civilization and its arts so fascinating to us, and so worthy of our study and emulation.

Fifth Dalai Lama

རྒྱལ་བ་ལྔ་པ།

7" x 7" x 5 1/2"Dimensions:

- Object / Type: Sculpture

- Century: 17th Century

- Orgin: Tibet